Debbie:

Atlantic hurricanes, for example, originate off the coast of West Africa,

where "tropical disturbances" form in low-pressure zones.

A disturbance

may intensify into a "tropical depression," surrounded by a high-pressure

zone that helps contain the storm, which is centered on a column of rising

air. Winds are moderate: 21 to 35 miles per hour.

Once the

winds exceed 35 miles per hour, the system, now called a "tropical storm,"

gets an alphabetical name. The storm now has the circular structure of

a hurricane, although it may not become one.

Powered

by solar heat that was stored in the ocean and then transferred into the

warm, moist air, the tropical storm becomes a hurricane once winds exceed

74 miles per hour. (More on hurricane formation.)

You might

expect a rotating storm to whirl itself apart, but hurricanes feed on themselves

to gain strength. In their energy flow, hurricanes resemble large thunderstorms.

But while thunderstorms can start over land or water, hurricanes only start

over water. Hurricanes also last much longer, carry far greater energy,

and cause much greater destruction. (More on storm comparisons and hurricane

formation.)

Tropical

cyclones are powered by heat engines -- "machines" that use heat to do

work. In a hurricane, the work comes in the form of driving furious waves

and winds. The hurricane sucks in warm, humid air from the lower atmosphere.

The air rises and condenses, releasing water vapor and the stupendous amount

of heat energy that the moisture absorbed as it evaporated from the ocean.

Finally, the storm exhausts this expended air into the upper atmosphere.

Define "stupendous"?

The average hurricane releases heat energy equivalent to 200 times the

global production of electricity! This released heat drives hurricane winds

and powers the upward convection in the storm (convection is the movement

of lighter fluids over heavier fluids). The rising air creates a low pressure

area near the ocean that draws in more energy-laden air, feeding the continuing

storm.

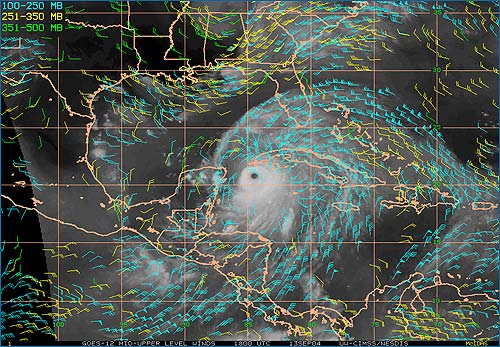

Due to the

Coriolis effect, the lower levels of a tropical cyclone start rotating

counter-clockwise in the Northern Hemisphere, but clockwise in the Southern.

Hurricane

winds whirl around the bizarrely calm "eye," a circular region with little

wind, no rain and often a blue sky. The placid eye is surrounded by a circular

"eyewall" of furious, thunderstorm-type clouds and the fiercest winds.

When Hurricane Camille shredded the U.S. Gulf Coast in 1968, winds in the

eyewall reached 200 miles per hour.

Sept.

4, 2004, Freeport, Bahamas: Hurricane Frances snapped trees, tore up roofs

and flooded parts of Grand Bahama Island. AP

Photo/Andres Leighton Sept.

4, 2004, Freeport, Bahamas: Hurricane Frances snapped trees, tore up roofs

and flooded parts of Grand Bahama Island. AP

Photo/Andres Leighton

Gargantuan

winds, combined with extremely low atmospheric pressure near the eye, cause

a catastrophic rise in sea level called a storm surge. This destructive

mound of water, topped with furious, wind-whipped waves, can hoist the

surface 20 feet above average sea level, causing biblical-scale flooding

along coastlines. In 1899, the Bathhurst Bay hurricane produced a record

record storm surge of 13 meters!

A storm

surge in New Orleans could spell disaster -- the city is well below sea

level, and flooding could be catastrophic. As we write, the city has already

begun to evacuate in anticipation of Hurricane Ivan.

Although

storm surges are the most dangerous element of these storms, water causes

another problem: All that condensing moisture eventually falls as torrential

rain. Although hurricane winds slow as they move inland and become deprived

of energy, rains can still be drenching. The record rainfall inundated

Reunion Island in the Indian Ocean in 1966. In 12 hours, a 'cane dumped

45 inches of water!

Hurricanes

come, and hurricanes go, but the overall trend is periodic lulls, followed

by a series of gangbuster years, like the present.

September

11, 2004, West Melbourne, Fla.: Emergency rescue team member Tom Branco

hands out water after Hurricane Frances.Photo:

Jocelyn Augustino, FEMA

Even though

hurricanes don't seem to be getting more intense, damage is increasing,

mainly because of development and torrid population growth in prime hurricane

country: which in the United States includes the Carolinas, Florida and

the Gulf Coast.

The threat

extends further up the Atlantic Coast. A huge storm around New York City

could funnel a 30-foot storm surge toward the city, flooding auto and subway

tunnels and causing fearsome destruction.

|

|